Along with writing novels and pieces for my blog, I am an assistant editor for Résonance, which as the title of this piece indicates, is a Franco-American Literary Journal.

For readers unfamiliar with Franco-Americans, here is a brief history: from the mid-1800s to the 1930s, there was a huge migration—almost a million from Québec— of French Canadians to the United States. They came to farm and to work in the factories and forests and settled primarily in New England. On my mother’s side, my great-great grandparents, Prudent and Demerise Jacques, bought land in northern Maine and grew potatoes.

Many of the French Canadian immigrants were dark haired and had olive complexions. They all spoke French—indeed French was my mother’s first language—and by and large, they were Catholic. In short, they were foreigners and were looked upon with hostility by the dominant Yankee culture in New England. One newspaper described Franco-Americans as “a distinct alien race.”

In Maine in 1919, a law was passed outlawing French in public schools except during formal language classes. In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan was a huge presence in Maine, and they marched against the Franco-Americans.

It wasn’t until 1960 that the 1919 law was repealed, and by then the damage had been done. Franco-Amercians had effectively been silenced, forced to abandon French so that their children wouldn’t be punished at school. A Franco acquaintance, who was caught speaking French on the playground, told me how she had to stay after school and write “I will not speak French at school” on the chalkboard. Until the day my mother died, she maintained that she spoke “bad French.”

This silence extended to other areas of life. For the most part, Franco-Americans kept their heads down and worked hard, very hard, and were perhaps too passive, as one elder Franco-American put it. Outside of family circles, stories were seldom told. We were dubbed “The Quiet Presence,” a source of ridicule and jokes about how stupid we were. (Unfortunately, I have heard more than my fair share of dumb Frenchmen jokes.)

Then came my generation. We were sick of being quiet, of keeping our heads down, of feeling as though we were congenitally stupid. We have organized into groups celebrating our heritage, sometimes through performances. Slowly, slowly, books, articles, poetry, and essays have been written.

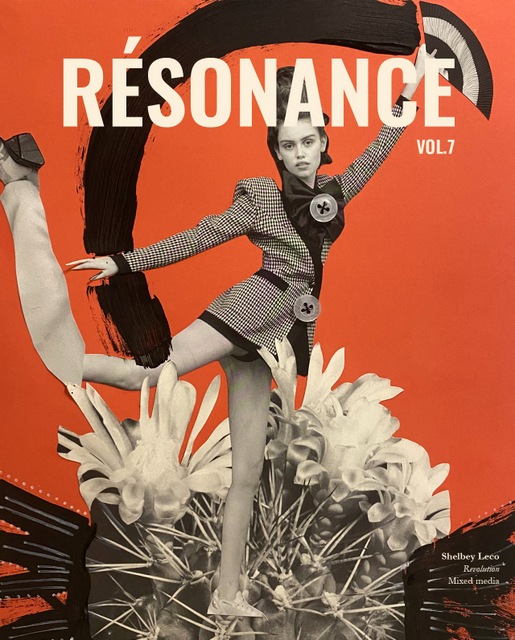

And under the auspices of the University of Maine at Orono, we have our very own journal, Résonance, which features “creative works by established and emerging writers, primarily by and/or about the Franco-American communities of the United States.” The newest issue, Volume 7, has just been published.

I help edit the creative non-fiction pieces. In this volume, there are a variety of essays, ranging from an account of the author’s ancestor arriving in Canada in 1662 to a humorous piece about a mouchoir (a handkerchief) to a reflection of nature and trauma to a reckoning of how French is spoken in Maine rather than in France.

In addition, there is artwork, poetry, fiction, and an interview with Susan Poulin, a Franco-American performer. If you have time, I hope you will check out Volume 7 of Résonance.

And for readers interested in submitting pieces to the journal, please check out the guidelines.

As we would say in French, à bientôt!